By Renée Evers

When my parents didn’t feel like cooking, it was sometimes suggested to “just walk to the Chinese” for a takeaway. Close to my parents’ house, on the corner, between the bike shop and the pub, there was a Chinese-Indonesian restaurant. As a child, I always wanted to go with them to pick up the food because I would get a piece of kroepoek from the nice lady behind the counter.

Whole generations will recognize stories like this. Who didn’t grow up with the white plastic containers wrapped in gray paper with a plastic bag around them? The presence of Chinese-Indosesian restaurant culture has become so normalized in the Netherlands that it has been included in the Inventory of Intangible Heritage since February 2021. The Chong family, founders of one of the first Chinese restaurants in the Netherlands, was proud of this spread of Chinese-Indonesian culture throughout the Netherlands: “Every village has a church and a Chinese!”

Chinese immigrants

The story of Chinese-Indonesian restaurant culture in the Netherlands begins before the war. Chinese immigrants were brought to the Netherlands in 1911 to act as replacements for striking Dutch sailors. These Chinese immigrants mainly worked in the port cities of Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Accordingly, the first Chinese restaurant, Cheung Kwok Low, was established in the Rotterdam port district of Katendrecht. This first restaurant catered to Chinese port workers who missed the taste of home while in the Netherlands. A Chinese restaurant in Amsterdam called Kong Hing followed in 1924.

‘I’ll have cat, please’

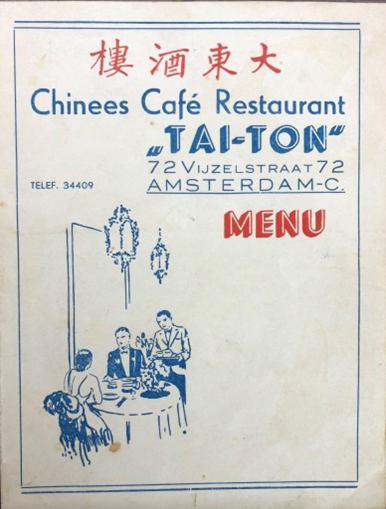

After the crisis of 1929, many people, including Chinese port workers, lost their jobs. As a result of this financial crisis, the remaining immigrants had to look for other ways to make a living. Some Chinese began selling peanut cookies on the street (this is where the offensive term “peanut Chinese” comes from). Other Chinese got into the restaurant business. Due to the crisis, international trade had declined, reducing the number of Chinese workers in Dutch port cities. As a result, Chinese restaurant owners were forced to attract a wider audience by offering Dutch food on their menus in addition to Chinese dishes. For example, the menu of Chinese Café Restaurant Tai-Ton from 1943 shows that it also served potatoes with groats. Special stories circulated about these early restaurants, with some people even claiming that cat meat was on the menu.

No ‘Chinese’ without Indonesian food

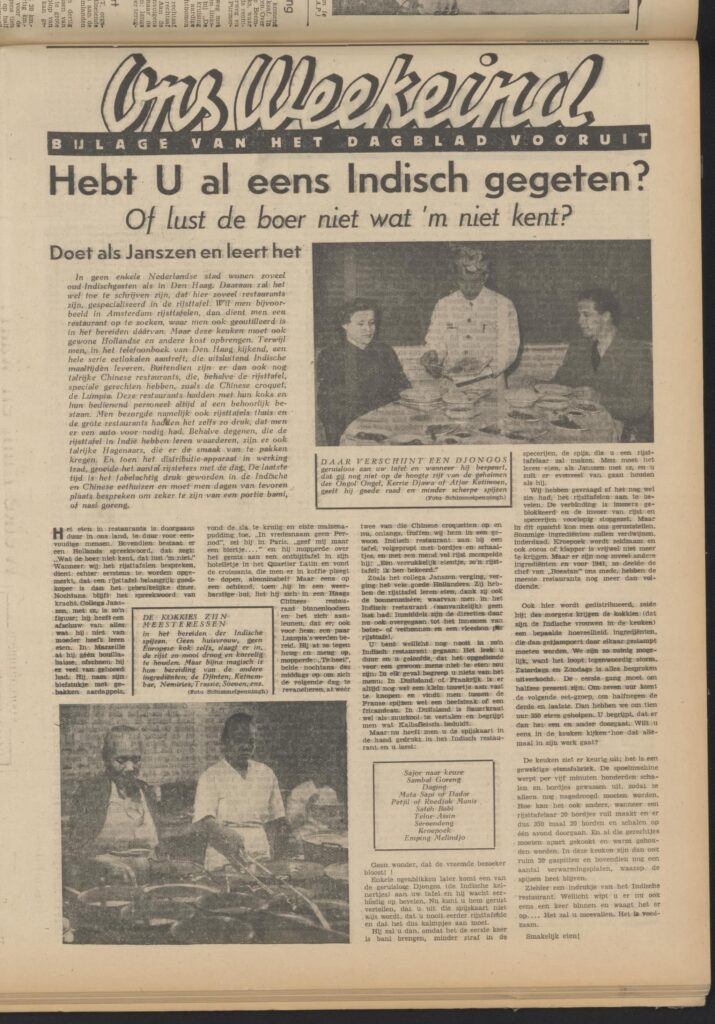

After World War II, the popularity of Chinese restaurants increased. The rise in popularity was linked to postwar effects. Due to the decolonization of the Netherlands East Indies, many people from the Dutch East Indies came to the Netherlands, including Dutch military personnel. They had become accustomed to Indonesian food and the Chinese food that had been introduced in Indonesia. Once in the Netherlands, there was significant demand for these Asian dishes. To meet this demand, Chinese restaurants hired kokkies, Indonesian chefs who taught Indonesian dishes to the Chinese cooks. In this way, a blending of Chinese and Indonesian cuisine emerged, adapted to Dutch preferences.

Daredevils

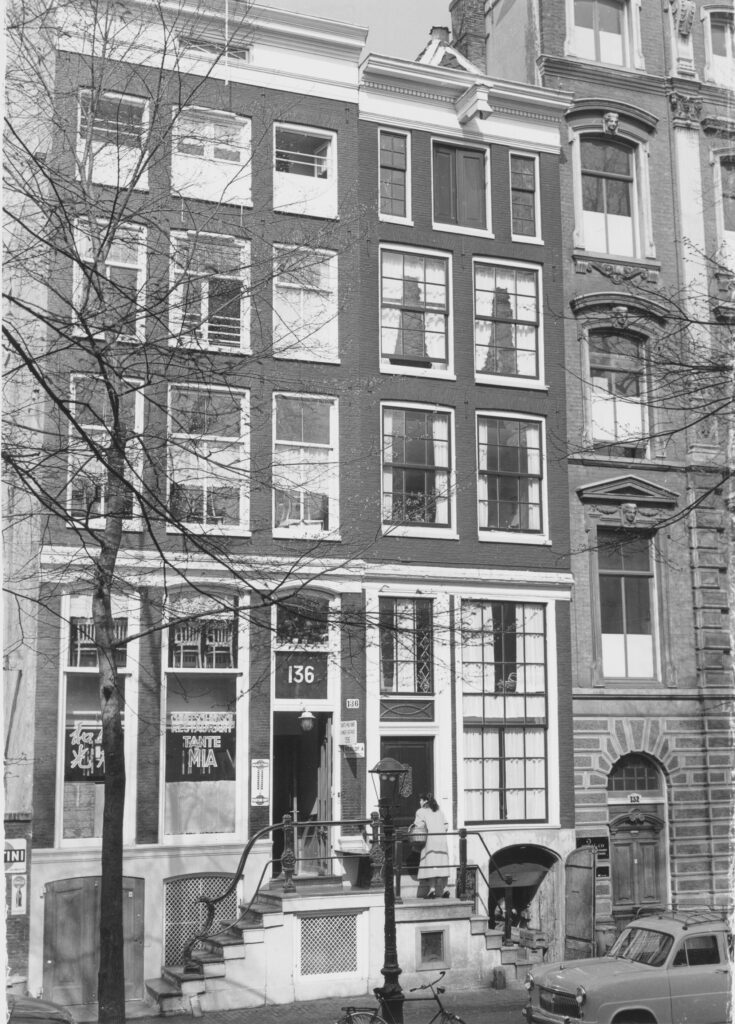

The first people who “dared” to eat at Chinese-Indonesian restaurants were mostly students and artists. At the Chinese, you could get a lot of food for little money. Tante Mia was one of the first Chinese restaurants in Amsterdam to serve nasi and noodles, and that for only 60 cents, in her living room! These “daredevils” spread their positive experiences about Chinese-Indonesian restaurants, which led to more and more people being curious about this exotic cuisine. In the 1950s, eating at ‘the Chinese’ became the first real experience of “eating out” for many Dutch people. If there was something to celebrate, you went to the Chinese. This was mainly because the low prices made it affordable for many social strata. And if, as a poor Dutchman, you still couldn’t afford ‘the Chinese’? You could come by with your own pan, which would then be filled at the takeaway for less money

‘No, I’m not eating that’

After years of potatoes, vegetables, and meat, some Dutch people found it incredibly daunting to try those unpronounceable dishes with numbers in front of them. To accommodate Dutch tastes, the dishes were made less spicy, and the portions were made larger. The Dutch like their food cheap and plentiful! Still, it often happened that groups of diners included one or two people who did not dare to try the Asian dishes. Ling Nam, the daughter of a man who opened a Chinese restaurant in Rotterdam in 1957, mentioned that her father had ‘normal’ steak with fries and vegetables on the menu for such cases. For difficult lunch eaters, he could make an omelet.

Ups and downs

Starting in the 1960s, the love for the vernacular “Chinese” continued to grow. During this period, restaurants with other ethnic backgrounds, such as Italian, Greek, or Spanish restaurants, also emerged. Although the percentage of Chinese-Indonesian restaurants relative to other establishments declined, the absolute number of Chinese-Indonesian restaurants continued to rise. In 1980, there were as many as 2,300 Chinese-Indonesian restaurants nationwide.

Yet, it has not been an endless success story for the Dutch Chinese. In 2012, the Netherlands still had 1,769 Chinese-Indonesian restaurants, but by 2023, there were only about 1,200 left. This decline is not due to a lack of visitors, the Dutch still love Chinese-Indonesian food, but rather a shortage of staff, particularly a shortage of Chinese cooks.

The love for Chinese-Indonesian cuisine is deeply intertwined with Dutch food culture, making it rightfully part of the country’s intangible heritage. The Chinese-Indonesian recipes, adapted to Dutch tastes, are the result of years of influence from three different culinary traditions. To conclude, I quote singer Frans Bauer, who, during a TV show in 2019, discovered that Chinese food in China is indeed nothing like Chinese food in the Netherlands. He said, “You won’t believe this! I have never eaten so little Chinese as I did there!”

Hungry for more Chinese-Indonesian cuisine information?

- Andere Tijden, De culinaire revolutie van de jaren 60

- Wereldmuseum Amsterdam, Hoe chinees is chinees eten?

- IsGeschiedenis, De geschiedenis van de ‘afhaalchinees’ in Nederland

- Allard Pierson, Menukaarten in de oorlog

- De Kanttekening, Hoe de eerste Chinezen zich in Nederland vestigde

- Trouw, De klassieke afhaalchinees verdwijnt: Hoelang is er nog een Chinees in iedere stad en ieder dorp?

- De Stentor, Chinees restaurant steeds zeldzamer in straatbeeld, maar verdwijnen? ‘Foe yong hai: niets aan veranderen’