By Machiel Spruijt

How does access to huge amounts of new data change the way historians work? Or, more specifically, how should historians make use of the new and various types of data that has become available online? These are some of the questions posed by Tim Hitchcock on his blog post ‘Big Data for Dead People: Digital Readings and the Conundrums of Positivism’.

The problem that Hitchcock poses concerns the danger of using ‘big data’ in such a way that it doesn’t do anything new. After all, historians have done a great job in using sources the traditional way. So the question is if big data could change anything, or that all it does is make research for historians easier. In other words, is it possible to ask computers a question that couldn’t be answered using the traditional historical tools? Hitchcock acknowledges the difficulty of this question, but he does think it is possible to do more than support traditional research with new digital tools. At the same time he warns historians of the dangers of being driven by new technologies instead of being served by them. So somewhere between not using modern technologies in a useful way at all and using these technologies on their own without critical reflection there is a middle ground. But, as we shall see, this middle ground is very easy to miss.

Let us return to the title for a second: Positivism. The belief that true science should be based on facts that are derived from empirical evidence. 1 + 1 = 2, that is a true, positive, fact. When Google Ngram shows us the quantity of a specific word in a specific year, it is a fact. There is a lot to be questioned about that fact because we are limited to the used databases and we don’t know to what sources it is specifically referring to, but the numbers are a fact within the given limitations. In this way the ‘big data’ approach has its roots in positivism and the use of quantification. When big data tools tell us that a certain word in a certain text was used a 1453 times, that is a fact (given that the data was entered correctly, a big issue we’re not even going into right now). So what was this big movement that opposed positivism? Right: good old historism. William Dilthey explained the difference between positivism and historism as the difference between explaining (erklären) and understanding (verstehen). So while positivist sciences are trying to explain certain phenomena, the humanistic sciences are looking for a deep understanding of the subject. Historism holds the belief that it is not possible to quantify history in a useful way: quantifying does not lead to an understanding of history.

Now that the background of this article and the posed problems is becoming clear, Hitchcocks answer is actually relatively straightforward. He argues that historians should make use of all the modern tools available, but the goal should not be (positivist) explaining but (historist) understanding. The way to do this is to make use of something Hitchcock calls ‘Stuff’. The term Stuff refers to everything and anything we can use to uncover history. It is an attempt to broaden the definition of sources used by historians. While historical sources mostly consist of text and image, Hitchcock argues that there are many more ways to learn about the past. For example, historians could use geography, archaeology, climatology and, of course, big data. The goal here is to try and come as close as possible to the subject using all of this ‘Stuff’. The ultimate goal should be to almost recreate history, so that we could use all our senses to see, hear and feel the past.

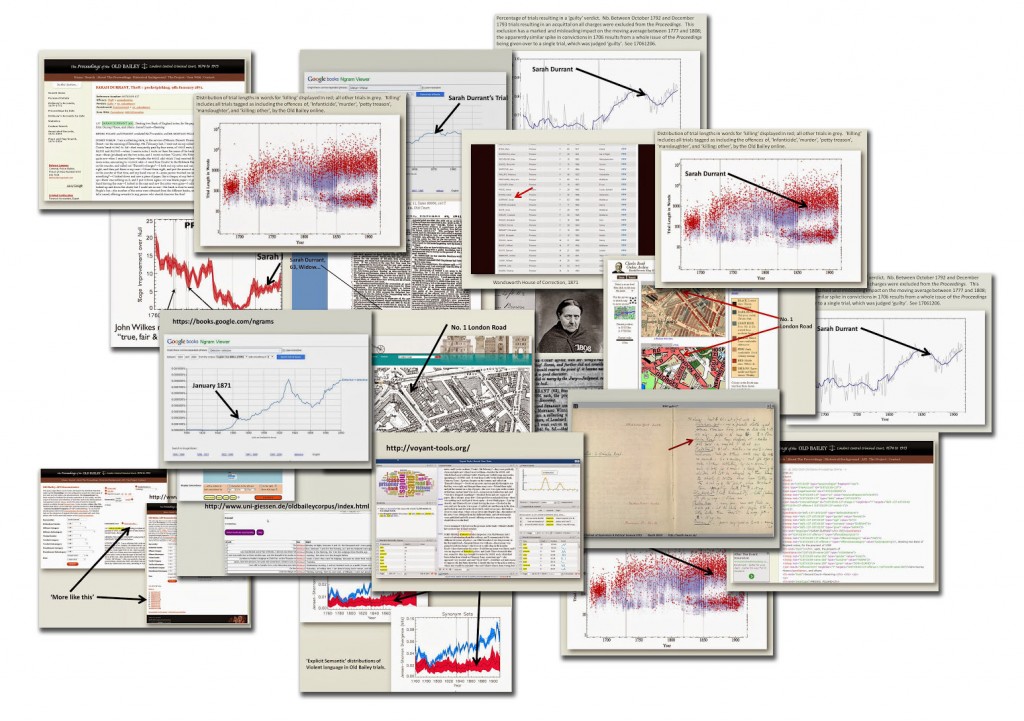

To give an example of this idea Hitchcock uses Sarah Durrant, a lady that stole some banknotes in 1871 and ended up in prison. Through all kinds of digital tools Hitchcock tries to show us how close we can come to her actual feelings, to understand Sarah Durrant. The thing is that for me he gives a poor example. Because the more big data sources Hitchcock uses, the more it starts to become a bunch of difficult numbers and statistics to me. He offers so much quantitative information that the reader gets lost in a maze of different tools, websites and statistics. And when Hitchcock offers his conclusions about Durrant, he places her in a big story about the processes of her time. So in the end we have learned very little of Sara Durrant the person. In other words, Hitchcock has explained very well how and why for example she got a quick prison sentence. But we are no further in understanding for example how she felt, what she was like or why she stole those banknotes.

I am not trying to say that Hitchcock failed in his example. He has shown very convincingly the way historians can use big data. But the irony is that in my opinion he gets stuck in exactly the same trap he warns historians about. The trap of using big data as a goal and not as a means to an end. But, to be fair, research itself is in the same way not a goal but a means to an end. So if Hitchcock were to use this research to recreate the life of Sarah Durrant in the way he proposes, using all senses to get an understanding of her life, then he would indeed have given a very fine example of the things modern historians are capable of.