Sharing feelings of pride or a sense of connection with others regarding specific cultural aspects of society is common all over the world. A particular example comes to mind quite close to home: Italian cuisine is a divine part of the day-to-day life of many Italians, and each region or city has its own rules concerning the preparation of meals or ingredients used. The differences between these particular aspects contribute to cultural identity, even though these unspoken rules are nowhere near being actual laws. However, it does exist in the culinary world that names are protected, and production processes are patented, especially in the world of alcohol. Due to the legislation around certain spirits, branding alone, bearing the name of that drink, is usually enough to guarantee ‘superior quality’ compared to similar drinks from outside the region or with slightly different methods of production. This blog post will shed light on two of those protected names: Tequila and probably the prime example of this phenomenon, champagne. This will, therefore, inform you on the strict traditions concerning alcohol production in France and Mexico. The identity of certain regions is intended to remain intact with the assistance of laws and regulations.

Champagne: a touch of class

Let’s start off with the most obvious example mentioned, champagne. This sparkling delightfulness is a drink for the rich and famous but the creation of this wonderful concoction actually happened on accident. The colder north of France wanted to imitate their neighbours in the south of France, especially in the Burgundy Region, and started making similar white wines. The only issue was the difference in temperature, which halted the fermentation (bacteria changing grape juice into wine) of the white wine bottles, a vital part of the process. The temperature started to rise again in the spring, causing a sudden presence of carbon dioxide gas in the white wine. This transformed the white wine into a bubbly delicacy.

Enough of this science lecture; you’re reading something written by a historian. Dom Pérignon, better known today as a very casual Monday evening drink that will cost you around 235 euros at your local Gall & Gall, was actually a French monk in the 1660s. This fair man purposely failed the first fermentation and added a second fermentation, leading to a drinkable white wine with bubbles. This is still the exact way champagne is made today and is therefore called the ‘Méthode Traditionelle.’ There is a general rule that only champagne may be produced in this fashion, but a few Proseccos, Cavas, and Crémants follow this same process. The only thing that is very strictly regulated in the world of sparkling wines is the use of the name champagne. This name is patented, and you can only call your product ‘champagne’ if it’s actually made in the region. This contributes to the manifestation of the exclusivity and high prices of champagne and reflects the pride (and almost arrogance) that the French feel toward culinary highlights like their champagne.

Tequila: the most memorable blackout

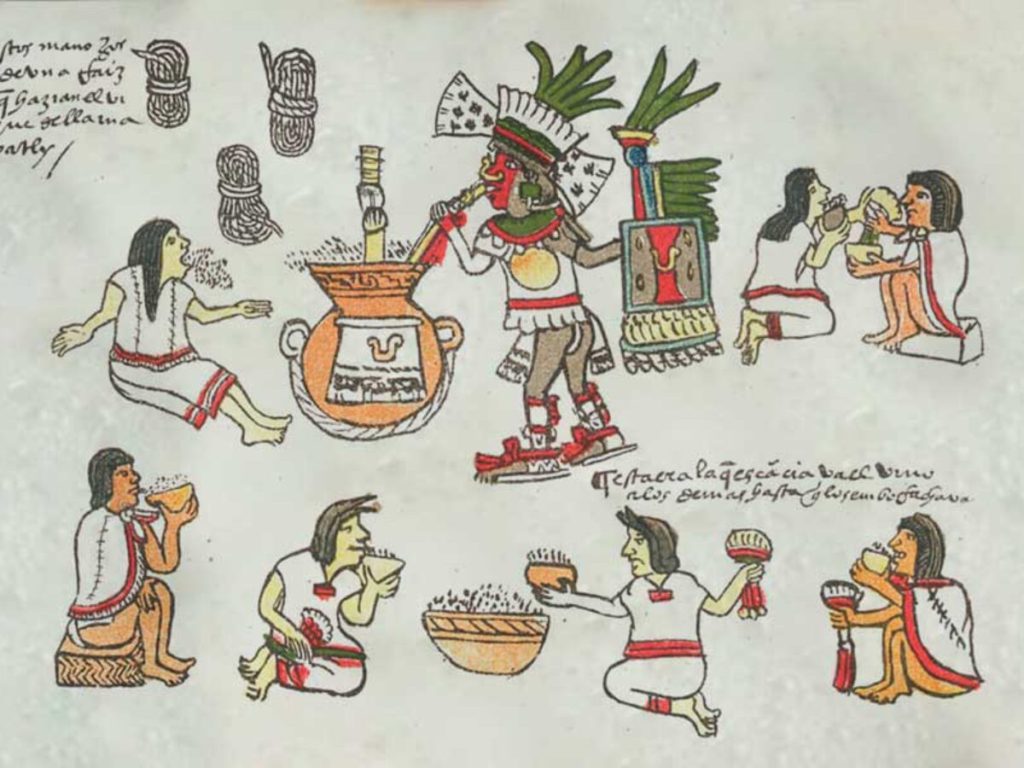

Ahora vamanos hablar un poquito de tequila, mi bebido favorito de Mexico. This is as far as I can go in Spanish, so it might be wisest to proceed in a language we all understand. There has always been a bit of a discussion about the predecessor of modern tequila. Some say the conquistadores were getting thirsty in the 1400s and 1500s when their supply of brandy ran out, and they started experimenting with mud and agave, a kind of plant native mainly to Mexico, which is still used in mezcal and tequila today. This mixture was similar to the mezcal of today, which is a drink similar to tequila. Way before the Conquest, the indigenous people of North Mexico, better known as the Aztecs, made an elixir called ‘Pulque’ from the juice of the agave plant. The conquistadores took pride in something they hadn’t even created themselves.

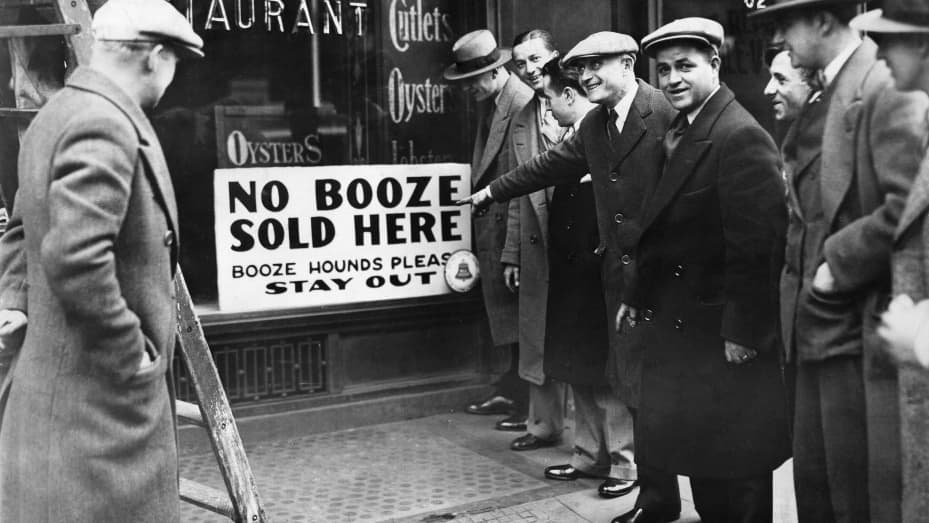

What we do know is where and when modern tequila came into existence. In the Mexican state of Jalisco, in a city called Tequila, the drink was named after the town and became very popular because of its geographically beneficial location on the route to the brand-new Pacific harbour of San Blas. This exotic drink suddenly became known worldwide, as the Spanish took it home and shared it with the rest of Europe. Its popularity increased even more during the Prohibition of Alcohol in the United States of America from 1920 to 1933. When Americans weren’t allowed to drink alcohol, they snuck out to places in North Mexico like Tijuana and managed to find a loophole in the whole Prohibition.

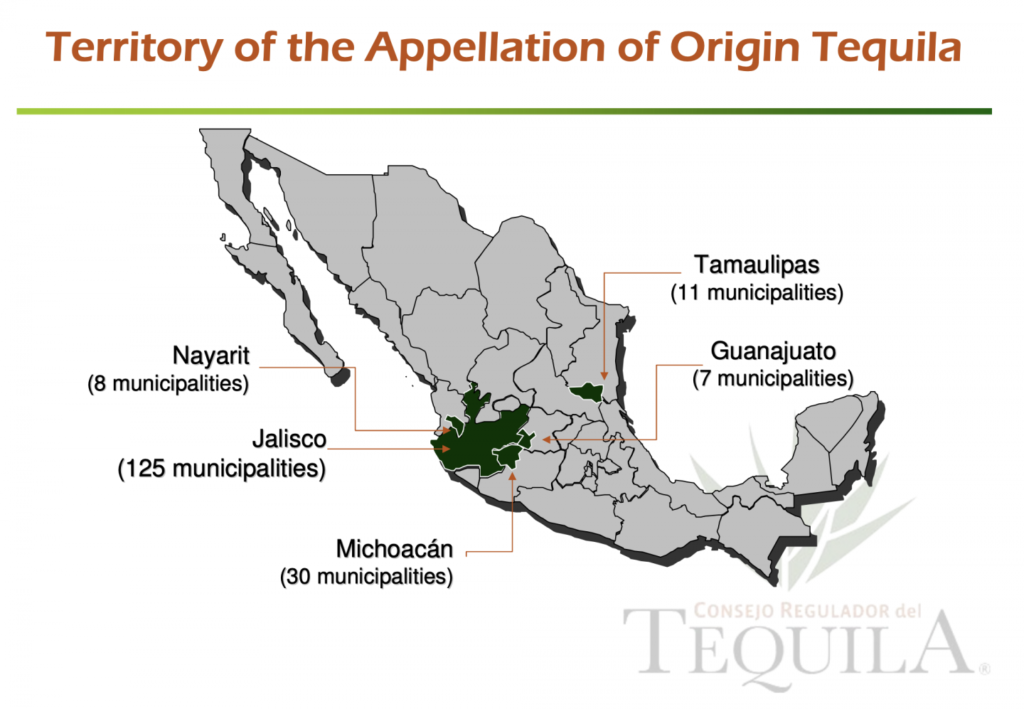

The development of Tequila goes hand in hand with important parts of the history of Mexico: their Aztec heritage, their relationship with the Spanish Conquistadores, and the United States of America. Mainly because of this, in 1974, ‘tequila’ became the intellectual property of Mexico. Unlike champagne, the fermentation of tequila is not limited to the town of Tequila. Most of the ‘Casas Tequilerias’ are found in the state of Jalisco, but there are also a few distilleries in the states of Guanajuato, Michoacan, Nayarit, and Tamaulipas. In this case, the origins of modern tequila could still be felt in Jalisco, but it also shows the nationwide love for the drink. Tequila became Mexico’s number one (legal) cultural export product, and that’s the reason why bars across the world are armed with salt and slices of lemon to ensure they give their guests the most memorable blackouts ever.

Drinks like champagne or tequila are significant parts of the cultural culinary identity of France and Mexico. The exclusivity of the name and production process is the best branding you could ask for. As you’re feeling pretentious drinking a glass of champagne or get your freak on doing shots of tequila, remember that you are not just drinking a spirit; you are experiencing a taste of history, culture, and identity.

Written by: Phillip Gale