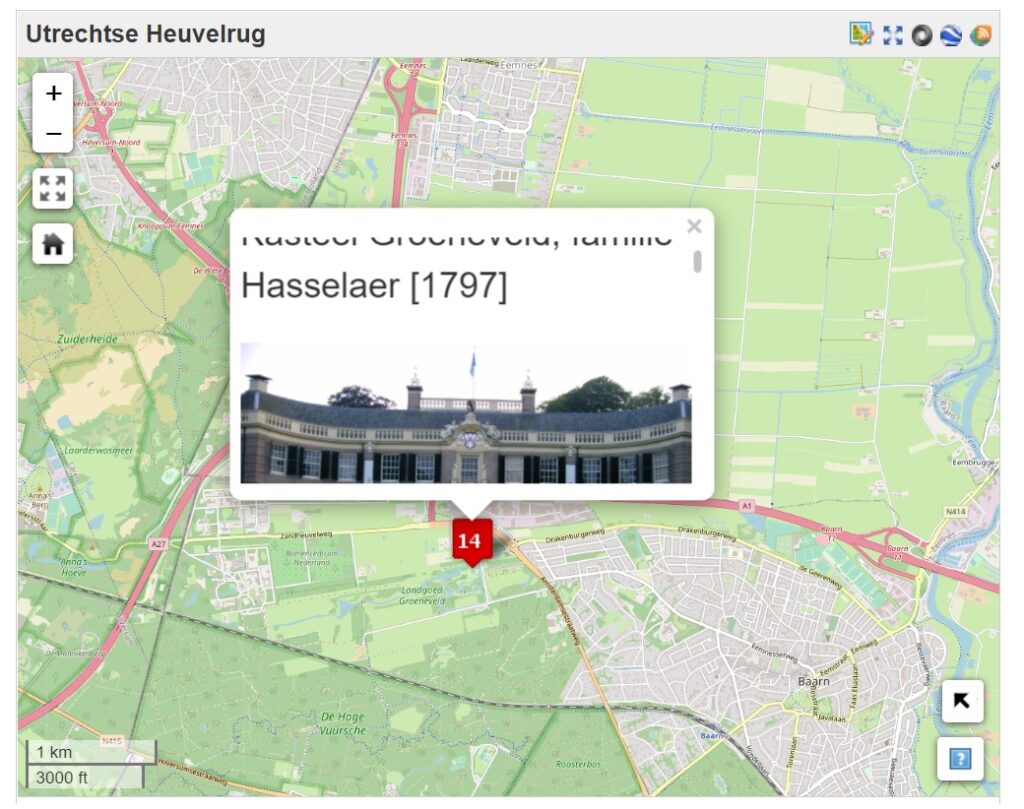

On the edge of my former hometown of Baarn lies a country estate called Groeneveld Castle. It is well known in the area because of its large so-called English landscape garden and interesting architecture. Many elementary school children in Baarn visited this garden to learn about nature or to take part in a scavenger hunt. It is also well suited for a nice stroll on a Sunday afternoon. I learned that Groeneveld Castle was built and inhibited by the “wealthy people from Amsterdam”, who built their country estates in the vicinity of Baarn to escape the busy city in the summer. But where did their wealth come from? When I saw Groeneveld Castle on the Mapping Slavery website, I wanted to know more. It turns out that the Hasselaer family, who owned the estate for a long time, was involved in the VOC and WIC. One of the later owners of the estate was Joan Huydecoper, who bought it in 1797. His father Jan Elias Huydecoper was one of the last directors of the Society of Suriname, a Dutch private company responsible for the administration of the colony of Suriname. One of their activities was to supply the colony with enslaved people.

Mapping Slavery

For many people in the Netherlands, the history of the slave trade is a far-off thing that happened a long time ago on another continent. Although there was no slavery in the Netherlands itself, there are many places that have links to this past. Whether this is a house of a plantation owner, an abolitionist or a place where a formerly enslaved person lived. It is the goal of the Mapping Slavery project to make these places known to a wider audience.

The Mapping Slavery project was initiated by Dienke Hondius, historian at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and is currently led by historian Nancy Jouwe. Several other historians collaborated on the project as well. It was funded by several institutions, including the Mondriaan Fund, the city of Amsterdam, and the Netherlands Consulate in New York. Its aim is to “include the history of slavery and the slave trade in local, national and regional history in Europe.” Nancy Jouwe said in the Groene Amsterdammer: “What we do is popular education. We think it is important that information about the Dutch history of slavery is shared broadly. In this way people will think and wonder about that history. They will talk more about it.”

The basis for the project was laid down in 2012, when a group of history students at the VU University created a map with the addresses of slave owners living in Amsterdam in 1863. The list of these addresses was compiled by historian Okke ten Hove and other researchers at the National Archives in The Hague and was based on the compensation records. These are records with former slave owners who were compenstated by the Dutch state for the loss of free labour at the time of the abolition in 1863.

The main part of the project are the maps that show the places that relate to slavery. These exist for the state of New York and the Netherlands. The map for Indonesia is currently under construction. In the Netherlands several cities are displayed, such as Utrecht, Delft and Middelburg. By clicking on a city or region, a map pops up with pins in different colours to show the places connected to slavery. The colours of these pins all relate to a certain aspect, such as abolitionism or black presence. You can even download the places and create your own tour.

Although the website makes a lot of information very accessible, the website itself looks somewhat outdated. Also the system of the pins on the map is not executed very well. The popups are quite small and barely fit the photographs and one has constantly to scroll to read the text. Bigger popups or external popus would have been more convenient.

Public History

The creators state on the website that Mapping Slavery is a public history project. The project definitely succeeded in reaching out to a wider audience. It has received extensive media coverage in the past, being featured on television, in magazines and on the radio. Many products have been created as part of the project. For example, guides about slavery heritage in Amsterdam, Utrecht, Groningen, New York and The Netherlands have been published. With such a guide in your pocket, you can walk through your hometown and discover places that relate in some way to the history of slavery. There are also a YouTube series and a podcast, not to mention the educative website and the related tours. For those who are interested in the history of the Dutch slave trade, there is a wealth of accessible material to delve into.

The Mapping Slavery project has succeeded in bringing together a vast amount of information about slavery in the Netherlands. It is a diverse collection of micro-histories that will be relatively unknown to most people. By showing concrete examples of places with a connection to the history of slavery, it makes this complex and sometimes abstract history much more tangible. You can see how the slave trade was woven into society. So next time I take a stroll through the garden of Groeneveld Castle, I will realize that also this peaceful park has a link to the Dutch history of colonialism and slavery.

Written by Hans Averdijk