For many countries it is a black page in history: the history of slavery. Fortunately, there is more and more open discussion and publication about this. The internet is a perfect place for this.

In this blogpost we will dive deeper into two slave registers: one of Suriname, one of the former British Colonial Dependencies. It will be discussed in the spirit of the work of Cohen and Rosenzweig.

A video about the digital publishing of the slave registers of Suriname. Credits: Radboud University.

Slave Registers of Suriname

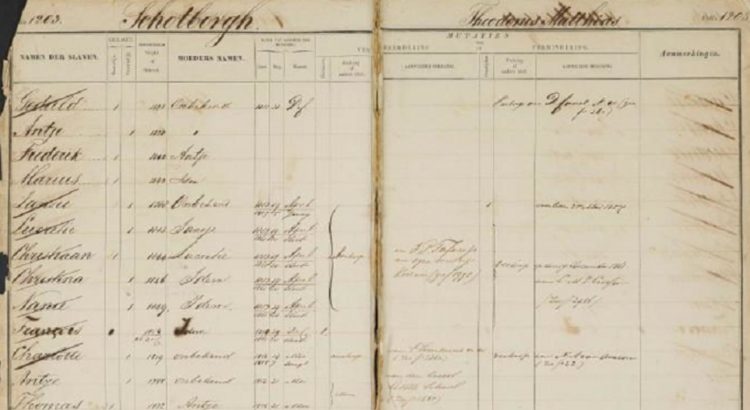

In June 2018 the Surinamese slave registers were made public. It was an initiative of the Radboud University. Seven hundred volunteers have digitized the data of more than eighty thousand slaves. These are the registers that were compulsorily kept between 1830 and 1863.

The idea behind digitizing the Surinamese slave registers is that the public can see what slavery has done to people, both before and after its abolition. It gives people the opportunity to explore their own family history. It also makes a dark period in history more transparant.

The slave registers can be found on the website of the Radboud University. The lists, of both the names of the slaves and the names of the plantations, can only be consulted as PDF files. Therefore, you cannot search by name. This makes it more difficult to get specific information.

The tools used on the website are limited. The most important reference is to the slave registers and the lists of names themselves. There is, however, a comprehensive justification about why the project is important. There is also the possibility to donate. Finally, there are also hyperlinks to other archival sites where much more information can be found.

Even though the project has already been published, you can still register as a volunteer to help digitise. As said before, you can also donate as a visitor, by means of crowdfunding.

Slave Registers of former British Colonial Dependencies

In the United Kingdom slavery registers of British colonies were also kept. These include slaves on Jamaica, Honduras and the Virgin Islands. These registers are also available online. The period covers 1813 to 1834.

Unlike the other project, the registers on Ancestry’s website can be reached by means of a search function. You can search by name, location, year and even gender and race/nationality.

The tools on the website are very extensive. With almost every search result you can also find images of the registers themselves. This increases the reliability and makes it easy for the public to verify and use it themselves.

A disadvantage of these registers is that you have to create a paid account for more options. Then you can also further examine the pedigree of a person. It is also not clear if you as a visitor can contribute yourself.

Conclusion

The publication of the Surinamese slave trade registers has a clear goal: they want to make the history of slavery public and transparent. Whether the database of the slavery registers of the British colonies had the same purpose is not clearly mentioned anywhere. The responsibility of the Surinamese slave registers is very strong. On the other hand, it is still difficult to search and limited in terms of information. It is of course only a few months online and can develop further, through more extensive information, more categorisation and more contributions.

The slavery registers of the British colonies, on the other hand, are extensive and easy to use. Here, however, it is not possible to make your own contributions, which makes it very abstract. The more we know